There is something different about Eastern storytelling. Someone who doesn’t watch anime or read Eastern literature might not notice at first glance. This doesn’t stop there it can be seen in many games, especially JRPGs.

Plot, Plot, Plot

Western storytelling is obsessed with progressing the plot as fast as possible. As if the only way a reader can be enjoyed or can take something away from the story is if something happens.

The important difference to compare the two is how they handle conflict. While Western storytelling often focuses on external conflicts and the resolution of those conflicts, Eastern storytelling places a significant emphasis on internal conflicts and the personal growth of characters.

In an article by Kim Yoonmi (김윤미), she highlights that “Unlike most 3-act and 5-act European stories, it[Eastern storytelling] heavily is based in self-realization, self-actualization, and self-development. Anything short of this in this story type are usually pretenders. It also often thinks of time itself as a circle.”

Moreover, Eastern storytelling tends to embrace ambiguity and open-endedness. It leaves room for interpretation and allows the audience to reflect on the story’s themes and messages. Endings may not always provide clear resolutions but rather invite contemplation and encourage personal reflection.

Story Structure

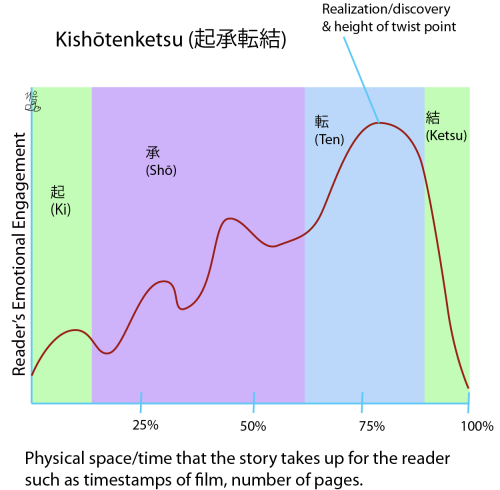

Japanese story structure typically follows the traditional Kishōtenketsu. This story structure is split into four acts: Ki, Shō, Ten, and Ketsu. The first part, Ki, is the introduction to the story. This introduces the reader to the setting, characters, and initial situation.

Shō develops the story and characters while the narrative unfolds. This section typically has a gradual buildup of tensions in the story and explores different problems and perspectives.

Ten introduces a plot twist or unexpected development that changes the story in some way. This is different from Western storytelling where this is typically the part where the conflict is solved.

The last part, Ketsu, concludes the story, often returning to the initial situation but with a deeper understanding and resolution of the character’s problems. Kishōtenketsu focuses deeply on the contemplation and reflection of characters, journeys, and personal growth, rather than the conflicts of the world.

Meanwhile, western storytelling focuses on the conflicts of the world rather than characters and has three to five acts: setup, rising, climax, falling, and resolution.

The setup establishes the initial situation, introducing the audience to the characters, setting, and central conflict or goal. This stage lays the foundation for the story and provides the necessary exposition.

As the story progresses into the rising action, tensions and conflicts escalate, and obstacles are presented to the protagonist. This section builds anticipation and engages the audience as they witness the challenges the characters face.

The climax is the turning point of the story, where the conflicts reach their peak. This is often the most intense and dramatic moment, where crucial decisions are made or major revelations occur. It serves as a culmination of the story’s conflicts and sets the stage for the resolution.

The falling action follows the climax and focuses on the consequences and aftermath of the events that unfolded. It provides closure to the conflicts, allowing for the gradual resolution of the story’s tension.

Finally, the resolution brings the story to a conclusion. It ties up loose ends, answers lingering questions, and provides a sense of closure for the audience. The resolution often provides a clear outcome, offering a satisfying ending to the narrative.

Unlike the circular structure of Kishōtenketsu, Western storytelling’s linear approach emphasizes cause and effect, building towards a resolution of the conflicts presented. While character growth and personal reflection are important elements in Western storytelling, they are often explored within the context of external conflicts and the overall plot progression.

Cultural Differences

Storytelling that is deeply rooted in Japanese culture, often emphasizes collectivism, harmony, and introspection. It values personal growth, self-discovery, and the interconnectedness of individuals within a community. This focus on internal conflicts and character development aligns with the cultural emphasis on self-reflection and self-improvement. As this video by Literature Devil puts it, “Die Hard would be nothing without a takeover of the tower, while in Goblin Slayer’s story could still exist without goblins, because the focus actually isn’t the goblins, its the character of the Goblin Slayer. It’s the world they live in and how the world reacts when there is a hero in it. A hero that doesn’t idolize glory or gold… that’s the true story of Goblin Slayer.”

On the other hand, Western storytelling reflects the individualistic nature of Western societies. It places a stronger emphasis on external conflicts, action, and the pursuit of goals. The hero’s journey, overcoming obstacles, and triumphing over adversity are common themes in Western storytelling. This aligns with the cultural values of individualism, competition, and the pursuit of success.

Overall, Eastern storytelling focuses on the character’s internal conflicts and does not depend on the external conflict that drives the plot to make a cohesive story. While Western storytelling focuses on external conflict and has a linear storyline that creates a story that focuses on the outside parts of a person, like goals and actions.